In Donald Haase’s “The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: A-F” Wolfgang Mieder uses the tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin to describe the practicality and efficiency of using folklore and fairy tale iconography in advertising. He likens the pied piper to a “symbol of the world of advertising” who would “play his pipe ever so sweetly and the consumers following him without resisting his charming and manipulative music.” While this is certainly true categorically of fairy tale-themed commercials, the tunes played and pipers playing them went through some drastic and experimental changes in the 1960s.

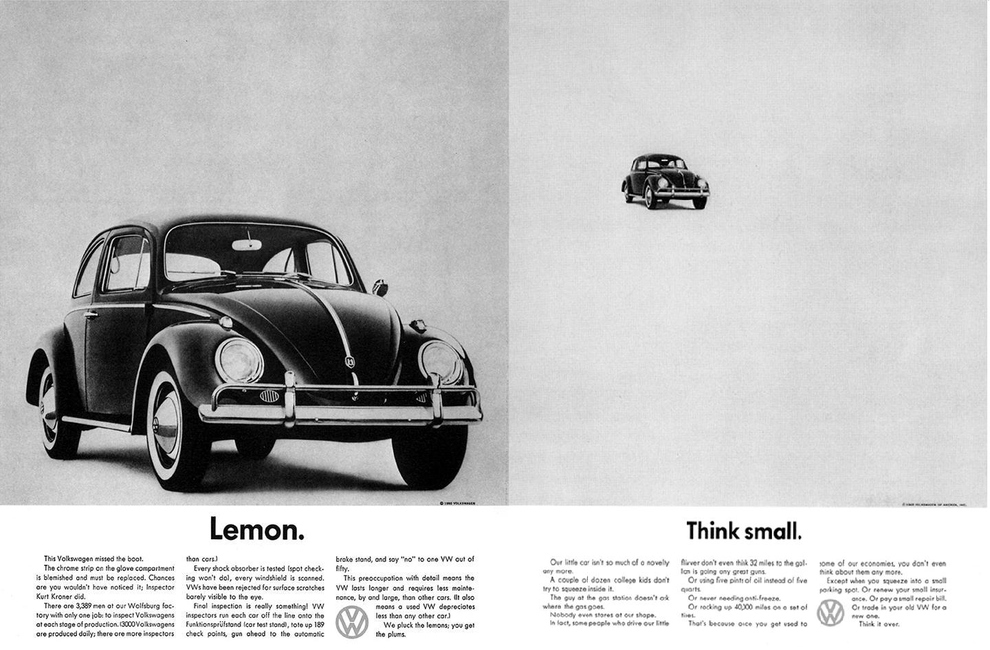

There are three key figures in the 60s advertising world that shaped the creative revolution: Doyle Dane Bernbach, David Ogilvy, and William Bernbach. Doyle Bernbach was the mind behind the infamous Volkswagen ad campaign that cleverly presented all the criticisms of VW’s cars as benefits. In his book “Confessions of an Advertising Man,” David Ogilvy began to establish a taxonomy for modern advertising—a taxonomy founded on ethics and honesty. And William Bernbach was one of the first advertisers to embrace the youth culture that was changing just about every other aspect of society in the 60s. Advertisers were getting to their audience through humor, honesty, and attempts at a genuine connection. The industry shifted from proclamations and lecturing consumers about their products to the idea of relationships and artistry.

In print media and on television there was a focus for increased visuals and less copy, less words. There was a desire to find new ideas, new characters, and new ways of selling products. Both the programing and advertising on television followed suit. Let’s take a look at this TV spot for Ajax laundry detergent soap featuring a fabled White Knight of European lore that straddles the line between the showing of the 60s the telling of the 50s:

The middle section betrays the energy and finesse of the start and end of the commercial. The TV spot ran in 1965, right when audiences were growing accustomed to the new, fast paced editing techniques while still familiar with the stilted delivery of 50s ad copy. In the 50s the White Knight would have been named, would have directly addressed the audience, or simply would have been more explicitly involved. Instead, the knight streaks across the screen and the audience is supposed to connect the dots themselves between the majesty of the hero and the cleaning power of Ajax.

Next, lets take a look at an advertisement that attempts to blend humor with a fairy tale figure. This time it’s the Fairy Godmother, breaking the fourth wall to publicize a prize giveaway from Crest in connection with the 1965 television broadcast of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella.

What works about this commercial is that the fairy tale connection is played only for laughs. The visible wires, the malfunctioning wand, and the Fairy Godmother speaking directly to the stagehands controlling the pulley system keeping her up undercut any sense of majesty, wonder, or actual magic typically used to push products via fairy tale figures. Sure, she speaks directly to the viewer, but she does so with energy and personality.

It would be misleading to say that all or even most commercials of the 60s strove for artistry over clarity or suggestion over description. Take for example this ad for Hidden Magic hair spray starring Wanda the Wonderful Witch.

This commercial operates like a 50s commercial in many ways (abundance of ad copy, directly addressing viewers, catchy jingles, etc.), but it does show some signs of its decade. For one the spot is live action as opposed to a cartoon. But for our purposes the most interesting and timely aspect of this ad is the character herself: Wanda the Witch. She was a character created whole cloth and not some existing figure shoehorned into a shoe commercial. She is undoubtedly modeled after Bewitched‘s Samantha (and even relies on some of the same trick photography commonly used on Samatha’s show), but there was at least some attempt to make her original. The same is true for Ajax’s White Knight (granted again it’s not much, but it is there).

Where the 50s relied on and named known fairy tale figures in TV spots, the 60s borrowed more iconography than characters. This mostly due to the artistic revolution sweeping creative fields. Following the late 50s debuts of Tony the Tiger, Mr. Clean, and the Trix Rabbit, demand was high for more original commercial mascots. The 60s delivered with still-popular figures like Ronald McDonald and The Pillsbury Doughboy. In general, the trend in the 60s was to rely on new, or at the very least more recently created, pop culture icons.

For the 1960s that meant instead of Red Ridding Hood and Cinderella hawking wares, TV audiences saw Alvin and the Chipmunks repping Post Cereal, The Muppets selling Dog Chow, Rocky and Bullwinkle pushing Cheerios, and Bugs Bunny as a mascot for baseball cards.

Check back later this week to learn how the fairy tale figures survived the laser age: the 1970s.