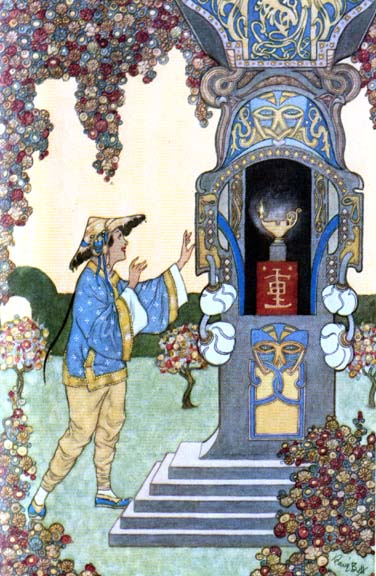

At first glance, Netflix’s Wish Dragon comes off as a cheap Aladdin knockoff transplanted into modern Shanghai. Instead of a plucky thief, we meet Din, a nineteen-year-old Door Dash driver, who longs for Li Na, a beautiful model and daughter of a wealthy businessman. His wish-granting dragon calls out these similarities. “Look kid, I get it you’re the peasant, she’s the princess, it’s a tale as old as time.”But the Aladdin similarities—coupled with the Chinese setting—were intentional. Director Chris Applehans was inspired to create it after a Chinese friend told him Aladdin had Chinese roots. The tale entered Western culture via Antoine Galland, a French writer and translator, who attributed it to a Syrian storyteller named Hanna Diyab. Early versions had Aladdin as a young Chinese man and illustrations showed him in Chinese settings. Fairy tales are best suited to the “long ago and far away,” and China is exotic to both France and Syria. A Middle Eastern tale could be set in China the same way an American story can be set in Europe. The greater the distance, the greater the wonder.

Producer Chris Bremble has stated that the goal of the Wish Dragon team was “to make world class animation in China for China…and the world” featuring “a strong Mainland China creative team, an international cast of talent, and a focus on the hopes and dreams of contemporary China.”

Everything about the film is calculated for cross-cultural appeal. Protagonist Din has a Chinese name, but when he needs an alias while posing as a rich man, he goes by “Dan,” a name familiar to Western audiences. Li Na can be palatably pronounced by Americans as Lina. Signs and products are labeled in both Chinese and English and songs switch back and forth between both languages.

Both of Din’s relationships—that with Li Na and his long dragon, Long, add depth and complexity to classic fairy tale relationship dynamics. Let’s take the dragon first.

The switch from genie to dragon helps anchor the story so firmly in Shanghai. Historically, Western dragons were scary, ferocious beasts in need of slaying and Chinese dragons were good and wise, though modern dragons of many cultures have become friendly to humans due to our sheer fascination with their power and allure.

Whatever creature he is, the classic magic servant lives to serve, or has no strong goals besides winning freedom from servitude. But Long comes with a backstory and an attitude. He used to be a human emperor before being transformed into a wish dragon to learn humility. Din is the last of ten masters he is to serve, and as soon as he’s done, he’ll regain his human form to enjoy a parade in his honor through the streets of Heaven.

While Aladdin’s Genie is playfully anachronistic, Long is confused by modern toilets, traffic, and cell phones. He’s not a ready and willing servant, either. His magic isn’t limited to the confines of someone making a wish, but he snaps at Din to make them faster so he can earn his parade faster. Din spends the first half of the film locked in a battle of wills with his servant, goading him to add extra frills on his wishes or use wishless magic for petty reasons (like flying them out of traffic to reach a party faster). Long comes with a maturity arc alongside Din’s. Din uses his first two wishes in pursuit of Li Na. One makes him rich for a day and another turns him into a kung fu master (Jackie Chan was one of the producers and it shows) to defend his dragon against goons who would steal him. When the eventual disappearance of his wealth leaves him unsuited to date Li Na, Din asks Long to make him rich permanently, but Long himself intervenes by showing him a flashback of himself dying alone and unloved as a rich emperor. With this as his example, Din chooses to save the wish for something that will bring Li Na happiness.

Magic notwithstanding, the hardest part of a fairy tale for cynical audiences to stomach is the fast-burning nature of fairy tale romances, which are designed to be whimsical and to get the characters together within the confines of a short story. When a tale is expanded to fit into a ninety-minute movie, this speed dating can feel rushed. Li Na and Din dodge this trope by starting out as childhood best friends, scrappy kids running around the slums of Shanghai before Li Na’s father’s entrepreneurial success forces her into an upscale neighborhood just after she has promised Din to be best friends forever. Din keeps the memory of her burning bright, even spending “date nights” alone on a rooftop beside a billboard featuring his friend’s face. And he still does think of her as a best friend, even though they’ve both grown older while they are apart. His goal for seeking her out is to have his best friend back, not to make her fall in love with him.

Long is alarmed to learn his master intends to use all his wishes around a girl. As in Disney’s Aladdin, magic can’t make people fall in love (or even in friendship). Though Li Na doesn’t recognize Din, he initially wins her over with his compassion and humor, but ruins it by taking advice from an emperor-turned dragon about how to act like a greedy rich person. Fortunately, their adventures jog her memory and the rest of the movie (and their advancing relationship) is informed by her nostalgia for the good old days when they were kids.

Wish Dragon is designed to appeal to a Chinese audience while still performing well for Western audiences. As Chinese as Aladdin’s roots may be, it’s still a tale highly familiar to American viewers, and the money themes, from Din’s work ethic in his delivery driving and the rich businessman repeatedly trying to steal his dragon, are built for conversation about a capitalist society. Any store built around wish-making carries with it a natural capacity to explore themes of wealth and greed. While this is primarily and intentionally an Aladdin story, there’s also a dash of King Midas towards the end, when an enemy captures Long’s magic teapot and wishes for a golden touch, leading to his own undoing. Midas is a Greek myth with no particular ties to China, but makes a thematically appropriate choice to enrich a story already built around riches.

It could, indeed, have benefited from even more outright, internal acknowledgment that it is trying to be an Aladdin story to help viewers read it as a script in conversation with historic source material rather than a simple rehashing. But though Wish Dragon can come across as a trite knock-off attempting to pass off a familiar story as something new, it is a highly conscious film with smart character dynamics built to successfully navigate East and West for maximized cross-cultural appeal.