In the new millennium the buzzwords of the first decade were globalization and technology. Across the globe the internet, computers, and cell phones were bringing people together and changing the way people lived their lives. A pair of studies at the start and the end of the decade showed a jump from 6% to 62% of Americans having in-home internet access. Cell phone popularity surged as well, fueled by advances in text messaging and mobile internet accessibility. In a very real way the world was changing.

These sudden changes didn’t come out of thin air—they had to be sold. And once again advertisers turned to fairy tale iconography to sell these new technologies. Using fairy tale stories to sell these innovative products was a natural fit, as Jack Zipes describes in his Oxford Companion, “basic fairy-tale elements like magic, transformation, and happy endings lend themselves perfectly to the advertiser’s pitch that the feature product will miraculously change the viewer’s life for the better. Product act as magic helpers who assist the heroes and heroines of the mini-fairy tale overcome whatever dilemma they face.”

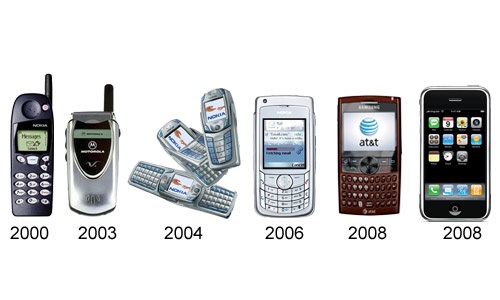

Cell phone commercials flooded the airwaves and haven’t left since. Fairy tales types like Hansel & Gretel and Cinderella were inserted into commercials for AT&T and Cingular Wireless to explain their miraculous features and to humanize the gadgets. And one particular commercial from Nokia went long by comparing their phones to all the different kinds of magic in the fairy tale realm.

In the commercial Nokia’s cell phones are described as magic wands, shining stars, and hidden treasures promising to reveal secret worlds. Cell phones are perhaps the best modern example of the product-as-magic pitch described by Zipes.

Even if the products advertisers were pitching weren’t as easily marketed as life-changing, they still combined this message with fairy tales. For example, this Mercedes-Benz commercial featuring Peter Pan.

In the ad Peter returns to a grown-up Michael and invites him come fly again. Smash cut to Peter riding shotgun while Michael drives a new Mercedes across the English countryside by moonlight. “It’s never too late to fly,” says Peter in the ad. In other words, it’s never too late to transform your life back to the happiness of youth through spending money.

Other cliches from previous decades like sexualizing fairy tale figures continued, as seen in this Pepsi One commercial featuring Kim Cattrall as Goldilocks with the Chicago Bears. On the flip side, commercials like this 7 Up Red Riding Hood spot pushed back on those genre expectations by having Red headbutt the wolf stand-in at the end of the commercial. And other commercials, like this one from Adidas, went for an artistically bold modernization with a stripped-down narrative.

The wordless and almost monochromatic ad (only the shoes are shown in color), focuses on style and tone instead of product or story. The commercial is selling a personality and not a product. Product descriptions had been slowly become obsolete, as a result of branding becoming the main focus of commercials decade by decade.

Meanwhile, Disney was successfully branding their fairy tale heroines as a collected franchise targeted at young girls and other companies were looking to share in the profits. Play Mobile marketed a fairytale kingdom Sleeping Beauty play set, but the advertising goes out of its way to avoid the phrase “Sleeping Beauty.” Barbie relaunched their direct-to-video film series with adaptations of the then-Disney free stories Rapunzel, Swan Lake, and Thumbelina, always releasing a new line of dolls to go along with the DVDs.

Fairy tales figures in popular media were becoming increasingly gendered while fairy tale stories were leaned on heavily to sell everyone on joining the new digital world. The 2000s was a brave new world, but it still had room for fairies.