One of the unique elements of TV is that they don’t have to market towards a specific group to buy their product, the way movies, books, or toys do, so they work to make a product that will attract as many viewers as possible across a much wider spectrum. Though children’s TV is created with children specifically in mind, the shows want to attract as many different types of children as possible. This makes studying gender patterns of characters and tales in children’s television interesting, especially when one gender becomes clearly more prominent than the other.

For my project on mashups I used every data point in the Channeling Wonder Database that is from a children’s television show and is tagged with more than one fairy tale type.

My first step in this project, which I outline in this post about my methodology, was to sort different tale types by elements like gender of main character. I expected most of the mashups would be like the Veggie Tales TV movie “Sweetpea Beauty,” which uses the stories and characters of Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Snow White, three stories of European traditional origin that contain princesses, magic, and castles.

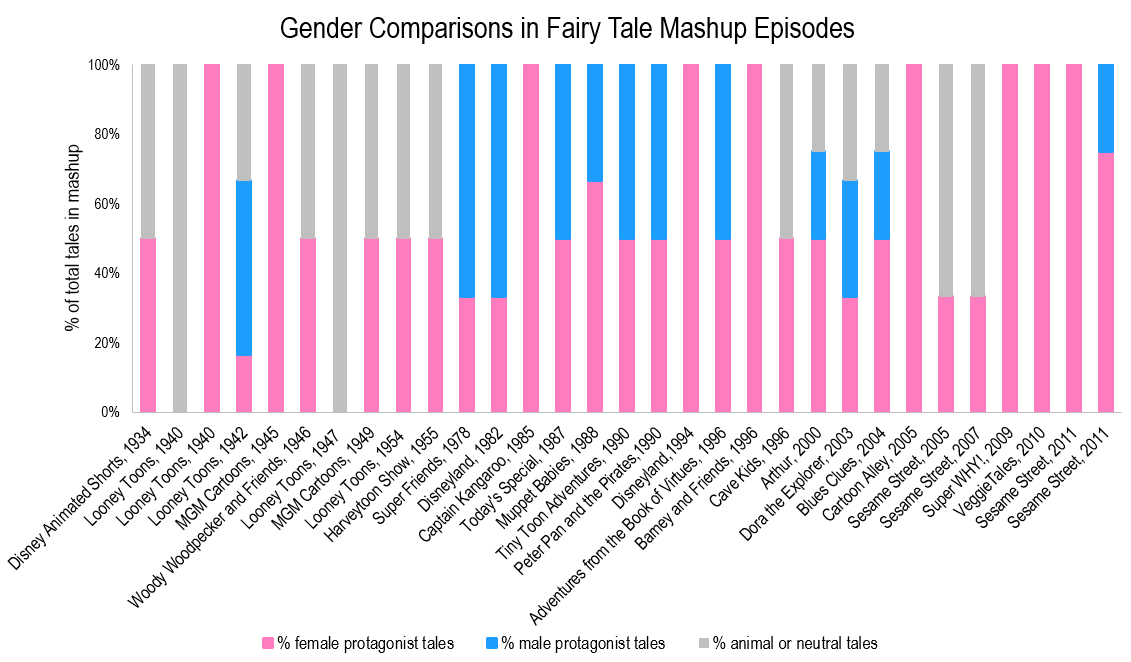

However, not all of the mashups were the types of mashups I was expecting. (Think how boring research would be if it always turned out how we thought it would!) To visualize my findings, I created the following graph visualizing the mashups as combinations of tales with female, male, or animal protagonists.

There are several trends contained in this graph. First, the female protagonists show up at a much higher rate than the male protagonists do (there’s more pink!), and are also increasing more than the male protagonists over time. As number of tales combined to create a mashup is rising over time, the number of male protagonist tales stays constant. This means as a whole, there is a higher percentage of female protagonists showing up in these mashup episodes over time.

To me, the most interesting thing about this graph is that, with the exception of two Looney Toons episodes which are made up of only animal tales, every bar has pink touching the bottom of the graph. There is not one case where only male-protagonist fairy tales are combined together, or where an animal tale and a male-protagonist tale are joined for a mash up. Why is this?

One knee-jerk explanation is that there are more common fairy tales that have girls in lead roles, but the data doesn’t support this. The top five fairy tales that are present in mash-up episodes on children’s television are (in order of frequency) Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, Jack & the Beanstalk, Three Little Pigs, and Three Bears. Two of these are female tales, one is male, two are animal. This diverse mix shows that it’s not a cut-and-dry “fairy tales are for girls” situation.

This prevalence of female-focused tales evident in this graph could be caused by the widespread oversimplification that princess = fairy tale, or that all fairy tales are targeted by default for girls. When TV decides to use fairy tales, they use a female tale as an access point to that tradition. I call this “the female anchor” strategy, and make the claim that these female-focused tales are chosen intentionally in order to connect the fairy tale approach to the wider fairy tale context that exists in our minds. Our assumptions about the femininity of fairy tales as a genre might be due to the Disney princess movies operating as our society’s most visible and influential fairy tales. Or, this could be caused by something even further back, the tales’ origination in the oral tradition that existed in nurseries, by kitchen fires, and in other domestic spaces that have been part of the female realm since long before anyone wrote down a single fairy tale.

This general association between femininity and fairy tales may cause creators of television mash-up episodes to feel that they need to include at least one female protagonist in order to ground them in the fairy tale tradition. If they are going to go out on a limb and really go for it with the fairy tale thing for one episode (the vast majority of these mashups are single episodes from a series that has little to do with fairy tales at the outset), they may feel they need one female character, a recognizable one with easy-to-read iconography like Little Red Riding Hood with her red cape, in order to tie them securely to that tradition. These female protagonists are used to effectively signal to viewers “This is a fairy tale episode. Adjust your expectations accordingly.”

I offer one explanation to this pattern, but there very well could be others. This could be a pattern based in fairy tale adaptation studies, the process and conventions of creating television, or more generally creating products meant for children. In fact, the issue of children playing roles in television meant for children is the issue I’ll be discussing next in this fairy tale mashup series. If children relate better to other children on television, how will that affect how television uses fairy tales with adult or adolescent characters?

Leave a comment