The following is a guest post written by Hannah Earl, a freshman in the English Department. This was a final writing assignment for Dr. Rudy’s Late Summer Honors course entitled Agency, Media, and “Tale As Old As Time,” then was workshopped with the FTTV team for publication on the blog. We hope you enjoy!

Blonde hair, blue eyes, a blue dress – these words describe millions of girls all over the world. This description also typically calls to mind the distinct image of Walt Disney’s 1950 Cinderella. It’s an image that inspired countless other versions of the tale in movies, television, and book adaptations of the story. This movie is both an example and a precedent of Cinderella being portrayed as blonde or “fair.”

Of course, fair-haired little girls identify with Cinderella because she looks like them. Cinderella in Charles Perrault’s “Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper,” which served as the literary source material for the 1950 film, is only described as being “beautiful,” Fairy tales have relied on visual images and icons like the glass slipper and the red apple ever since their existence in oral traditions and illustrated children’s compilations. When fairy tales are adapted into a moving image media like film or television, the visual iconography is expanded. From the description of a beautiful girl and a glass slipper present in the literary tale, our culture’s image of “Cinderella” has been expanded by this enormously influential film to be much more detailed: a beautiful, slim, blonde girl with a dreamy, gentle voice gets a blue ball gown with the glass slippers from her round, bumbling fairy godmother, assisted throughout by her crew of friendly animal friends. Each of these were decisions that Disney Studios made when adapting this tale into visual media, and somewhere along the line they decided that this beautiful girl is a blonde girl.

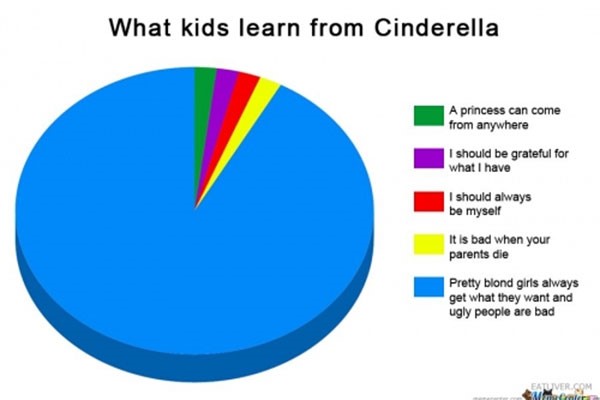

As a brunette, I was affected by this as a child. I thought I would be prettier if was blonde or that I’d have more choices with blonde hair since I would get more attention. Cinderella, other movies, and television shows reinforced this in my mind. Society tells children that blonde girls are prettier and more active, with more freedom because of “beauty.”

However, traditional Cinderella retellings actually don’t give the title character as many choices as I’d thought. When I reexamined the 1950 cartoon and the 2015 film, I discovered that Cinderella is actually a character who is more acted upon than one who acts. Others, like the mice and her fairy godmother, do things for her, which provides her with the opportunity to meet her true love. Cinderella is given things, like the dress and the carriage, instead of going to get them for herself. This portrays her as a passive character—a stereotypical blonde.

Partially due to the prevalence of the Disney film, we’ve been trained to associate the visual of blonde hair with passivity, so when an adaptation intends to work against that precedent in the plot by giving Cinderella a more rebellious and active role, they make this point visually with a dark-haired Cinderella. In Ella Enchanted, Ella must try to break her curse of obedience, all the while fighting injustice in her kingdom. In Ever After, Danielle has to take action when her stepmother tries to sell one of the servants to America. The Cinderella in Into the Woods has to deal with her cheating husband. Finally, in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s musical take on the story (three TV versions in 1957, 1965, and 1997), Cinderella is concerned with increasing the social justice in her kingdom. These four empowered, active Cinderellas stand up for what they believe in and act in opposition with the status quo. These adaptations are different from the Perrault story, but they all involve a Cinderella who frees herself from her circumstances.

The effect of intentionally casting brunettes in these alternate Cinderella stories is complimented by the step-mothers and stepsisters often being blonde as contrast. Take as example Ella Enchanted, Into the Woods, and the 1965 Rodgers and Hammerstein Cinderella TV movie. This aesthetic choice makes the main character visually stand out against her enemies. The Cinderella character in these adaptations has more agency.

Films need strong blondes and passive brunettes and everything in between in fairy tale media so that kids can know that there are different types of people with similar physical traits. This will help empower them to be whatever they want to be. We need to diversify how we cast our princesses with their personalities to banish these stereotypes. This will tell children that everyone can get a happily ever after, no matter what they look like.