We’re pleased to have Abby Elkins brings us the guest post this week from Dr. Rudy’s Applied English class from Winter 2017. Please enjoy!

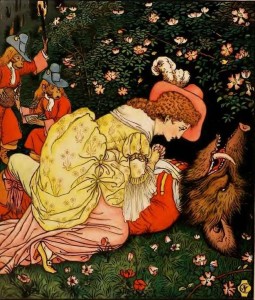

Apart from the fairy tale tradition’s classic damsels in distress, shines Belle, or “the Beauty,” from the story of “Beauty and the Beast.” Critics have argued that the story of “Beauty and the Beast” follows the traditional captivity narrative of a female succumbing to a stronger male character, however I argue that Belle’s choice to sacrifice herself in her father’s place and remain with “the Beast” shows strong feminist ideals and strength of character, which are further strengthened by the tale’s gothic roots and portrayal. In fact, the modern character of Belle originated in the 1700s from two female authors, Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont. Both women held feminist ideals ahead of their time. Belle has grown over the past three hundred years to further represent an intelligent and self-aware fairy tale heroine. This is seen w ith Cocteau’s 1946 film La Belle et la Bête, which emerged in the midst of the passive princess Disney era of Snow White (1937), Cinderella (1950), and Sleeping Beauty (1959). La Belle et la Bête, in contrast to these Disney films, shows a strong female protagonist with complete agency. Almost forty-five years later, Disney swooped in and built upon Cocteau’s adaptation to create an educated and proactive Belle in the 1991, Beauty and the Beast. Disney has released yet another adaptation starring gender equality advocate Emma Watson as Belle. Watson’s portrayal of a 2017 Belle shows an innovative heroine who is visibly not be wearing a corset.

ith Cocteau’s 1946 film La Belle et la Bête, which emerged in the midst of the passive princess Disney era of Snow White (1937), Cinderella (1950), and Sleeping Beauty (1959). La Belle et la Bête, in contrast to these Disney films, shows a strong female protagonist with complete agency. Almost forty-five years later, Disney swooped in and built upon Cocteau’s adaptation to create an educated and proactive Belle in the 1991, Beauty and the Beast. Disney has released yet another adaptation starring gender equality advocate Emma Watson as Belle. Watson’s portrayal of a 2017 Belle shows an innovative heroine who is visibly not be wearing a corset.

Understanding the progressive nature of Belle’s character is strengthened when considering her origins in the mid 18th century. 18th century literature primarily shows a narrative with increasing female passivity and tightening domestic encirclement including themes of duty, resignation and elegance. The 18th century also showed the emergence of the female gothic genre, characterized by gloomy castles, treacherous forests and feminine societal and sexual desires. M. H. Abrams defines the female gothic as an opportunity for women writers to attribute “features of the mode [of Gothicism] as the result of the suppression of female sexuality, or else as a challenge to the gender hierarchy and values of a male-dominated culture.” It is with this female gothic approach that both Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont composed their versions of “Beauty and the Beast.” They used their real-life experience to bring attention to societal and gender inequality through their stories.

Villeneuve was married in 1706 to Jean-Baptiste Gaalon de Villeneuve, a wealthy member of an aristocratic family. After just six months of marriage, she requested a separation of property from her husband, who had freely spent the majority of their inheritance during their first months together. Her husband died just five years later, leaving her a widow at age 26. Subsequently she lost her fortune, moved to Paris, became friends with famous playwright Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon, and began to support herself through writing. She published her version of “Beauty and the Beast” in 1740 in La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins, showing a royal Belle with magical powers. In Villeneuve’s version, it is Belle, the female protagonist, who has exclusive power to rescue the Beast and his kingdom from danger.

Beaumont also proves to be ahead of her time both in her literature and accomplishments. She was subject to an arranged marriage as a young woman and consequently left her “dissolute libertine” of a husband in 1746. In Beaumont’s version, Beauty is no longer a product of magic and royalty, but the daughter of a recently impoverished merchant. She is neither peasant nor royalty and this, plus the setting of her urban home, are unusual among fairy tales. Beaumont was alluding to and promoting the social changes occurring among classes in the mid 18th century. Critic Christine McDermott writes: “For particular social reasons, ‘Beauty and the Beast’ became the story everyone needed to tell throughout the 18th century. It addressed dissatisfaction with restrictive gender roles and the quest for Beauty to find her prince through the Beast became the representative of a female quest for the self in a repressive world.”

Beaumont also proves to be ahead of her time both in her literature and accomplishments. She was subject to an arranged marriage as a young woman and consequently left her “dissolute libertine” of a husband in 1746. In Beaumont’s version, Beauty is no longer a product of magic and royalty, but the daughter of a recently impoverished merchant. She is neither peasant nor royalty and this, plus the setting of her urban home, are unusual among fairy tales. Beaumont was alluding to and promoting the social changes occurring among classes in the mid 18th century. Critic Christine McDermott writes: “For particular social reasons, ‘Beauty and the Beast’ became the story everyone needed to tell throughout the 18th century. It addressed dissatisfaction with restrictive gender roles and the quest for Beauty to find her prince through the Beast became the representative of a female quest for the self in a repressive world.”

Almost two hundred years later, director Jean Cocteau released a gothic adaptation of Beaumont’s “Beauty and the Beast.” The following clip shows the Beast’s castle coming alive for Belle, which had previously remained dark and foreboding to the film’s male characters. Belle is the savior of the cursed castle and the film’s score welcomes her with a chorus of heavenly angels. This can also be symbolically viewed as Belle being a savior for women’s rights and gender equality.

Forty-five years later, Cocteau’s film served as almost direct inspiration for Disney’s 1991 adaptation of Beauty and the Beast. The 1990s show a drastic change in the stereotypical Disney princess character. Critic Keisha Hoerner published a study in 1996 comparing eleven Disney animated feature films and analyzing the different modes of behavior between female characters. She found that “more contemporary characters, such as Belle, show more vocalization in opposing unfair treatment they experienced compared to older characters like Cinderella and Snow White who suffered injustices without uttering a complaint.” Belle stands as a feminist character from the very beginning of the film with an opening musical number about her being an outcast in her French country village. The other women in the village are taking care of crying babies, baking, and throwing themselves at the masculine Gaston. There are three blonde women especially highlighted in the opening scene as contrasting Belle. They are triplets, dressed identically, show bare shoulders and skin, and live primarily to swoon over Gaston. In contrast, Belle is dressed conservatively, spends her time reading at the bookstore and spurns Gaston’s advances. She dreams of “adventure in the great wide somewhere,” and longs “to have someone understand, [she] wants so much more than they’ve got planned.”

contrast, Belle is dressed conservatively, spends her time reading at the bookstore and spurns Gaston’s advances. She dreams of “adventure in the great wide somewhere,” and longs “to have someone understand, [she] wants so much more than they’ve got planned.”

In Disney’s most recent adaptation of the tale, Belle, as portrayed by feminist Emma Watson, is even more progressive. She is independent, an inventor, an avid reader and strongly declares, “I’m not a princess,” when given a gown to wear. Both Belles also hold a unique capacity for kindness that their fellow villagers do not. They show compassion to their aging fathers and selfless sympathy towards the Beast. Although both Belles are physically beautiful, Disney places an emphasis on their beautiful and kind hearts. This move gives empowerment to women as the character Belle is not objectified by mere physical attributes.

Since the 1700s, the character of Beauty or Belle has brought light to women everywhere who gain hope from her strong choices, selflessness, inner beauty, love for knowledge, and unconformity. The continual and frequent adaptations of the tale prove its importance and invite women and girls to believe in themselves. The much desired “happily ever after” can be achieved in a myriad of ways and is not secluded to a typical “fairy tale” ending.