Cinderella is quite possibly the most popular story about a blended family in Western culture. Her ugly relationship with her stepfamily can provide an outlet for young viewers in messy or abusive step relationships. But stepmothers and their children have feelings just as real and complicated as the “Cinderellas” of the world and suffer from one-sided portrayals. The etymology dictionary website Etymonline says the very word stepmother has been associated with cruelty since at least the Middle English era. The stepmother in most adaptations is a tyrannical figure. She might be clever, but only so she can brainstorm ways to torment Cinderella all the better. Her daughters’ character traits are ugliness, cruelty, and such enhanced stupidity that they can’t recognize Cinderella once she gets dolled up. Biting comments towards the stepfamily are presented as excusable, whether coming from Cinderella or another character.

In the 1978 TV movie Cindy, stepsisters Venus and Olive present Cindy with a long list of chores to do before the dance. When they tell her their only chore is to make themselves beautiful, she snarks, “Looks like I have the easy list.” The prince later jokes that one of the stepsisters should volunteer to test nerve gas for the war effort. This is presented as comedy.

One of the stepsisters in the 1964 Warner Brothers Senorella and the Glass Huarache is ugly enough to crack a mirror. At the close of the cartoon, a man asks the male narrator whatever happened to the wicked stepmother, to which he miserably responds, “Uh, that’s the sad part. I marry her.”

Some animated adaptations care so little about the stepsisters that they are drawn as visually identical. Others cut the stepfamily out entirely in favor of a happy, fanciful narrative focusing on Cinderella and her prince. Big screen Cinderellas that paint at least one stepsister as sympathetic usually do so by further villainizing their mother. In the TV movie Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister, stepmother Margarethe is desperate for financial preservation for her daughters Iris and Ruth, the latter of whom has special needs. Margarethe and Iris strike up romances with a painter and a painter’s assistant respectively, but Margarethe makes the financially practical decision to marry a wealthy tulip merchant with a daughter named Clara. Iris and Clara’s relationship is one of jealousy. Margarethe tells her own daughter she isn’t pretty and Iris envies Clara’s easy life. When the tulip market goes south, Margarethe is back to marriage scheming, this time trotting out Iris for the prince. Clara isn’t robbed of her happy ending, though, and Iris is able to score one with the painter’s assistant.

In Ever After, stepmother Rodmilla gets some scant character depth when she alludes to having a harsh mother who sculpted her to become a marriageable lady. The generations repeat themselves. Her elder daughter, Marguerite, is a wrathful, spoiled pawn her mother parades before the prince, while the younger, Jacqueline, is a sort of backup-Cinderella. She’s kinder to her stepsister, Danielle, and sometimes gets recruited into chores when Danielle herself isn’t handy.

Rodmilla is notably more wicked that most other stepmothers, selling Danielle into sex slavery (she escapes) to keep her away from the prince. Jacqueline alerts the prince of Danielle’s plight and meets a boy of her own at the ball.

These movies are notable for fleshing out the stepfamily’s characterization, but a two-hour movie can only do so much for them. TV series are better equipped to examine the serious ramifications of Cinderella stories in contemporary settings.

A 2010 Korean drama brings the story into modern Asia and puts stepsister Eun-jo in the protagonist role. The show’s title is alternatively translated as Cinderella’s Stepsister or, less commonly, Cinderella’s Sister, both renderings of the word eonni. It’s an affectionate term meaning “older sister” which Cinderella gleefully applies to a stepsister who doesn’t want to hear it.

Eun-jo has grown up with a chronic golddigger mother and her string of scumbag boyfriends. All of her mother’s relationships end with them running away or getting kicked out, so she’s learned to emotionally distance herself from the boyfriends’ children. A chance meeting between Eun-jo and Hyo-Sun (Cinderella) results in their parents marrying, though they don’t initially register the marriage according to Korean law. Hyo-Sun is an annoying, socially awkward girl, the type to text her crush ten times to no response and think her cell carrier’s to blame. She’s not some spoiled princess caricature, she’s human. Hyo-sun is thrilled to have a new sister, until Eun-Jo rebuffs her overbearing attempts at sisterhood.

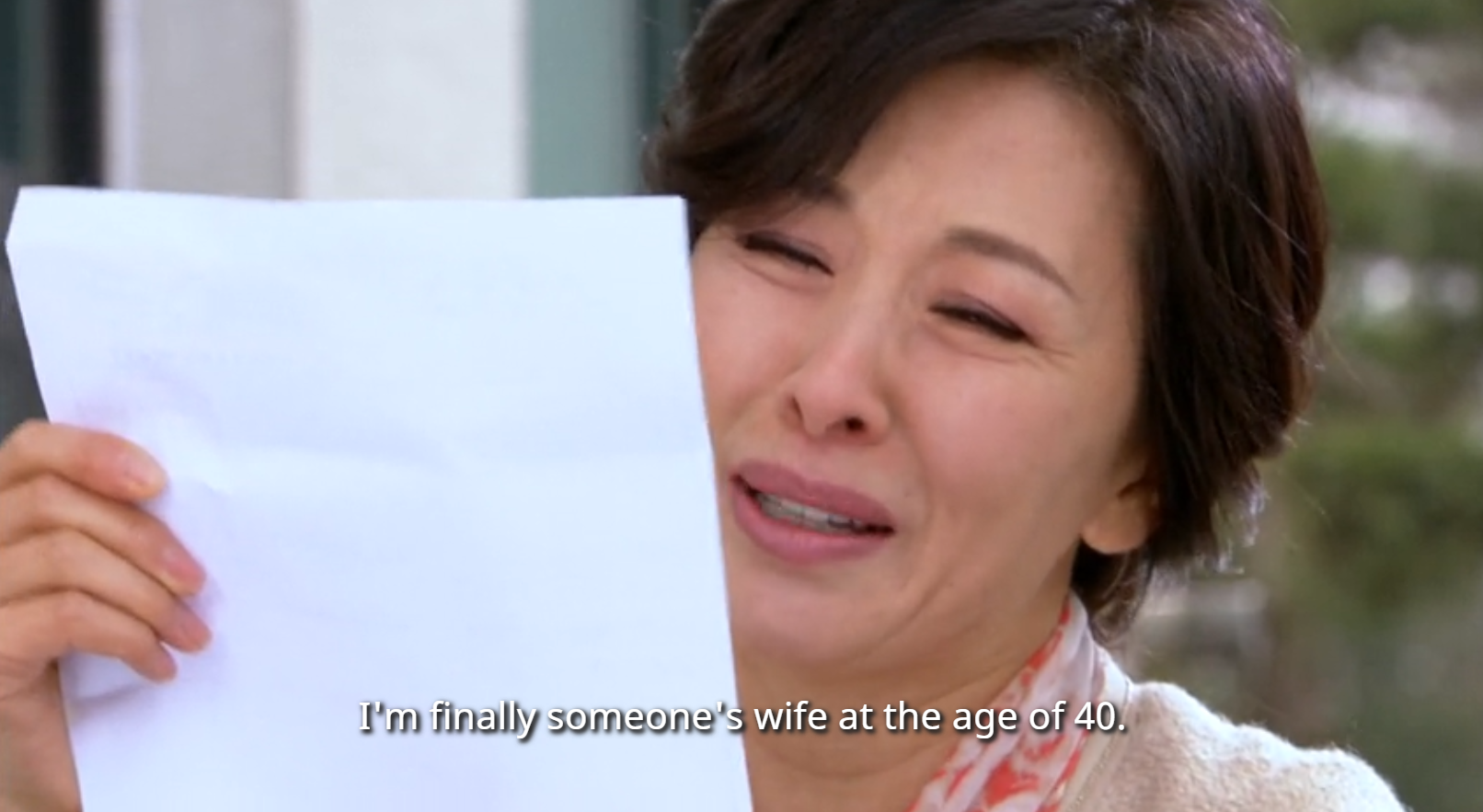

Stepmother Kang Sook, a master manipulator, is desperate to solidify her marital (and financial) status. She convinces Hyo-Sun’s father that the girls are the target of schoolyard gossip because they have different last names. He registers their marriage, which moves Kang Sook so much that she ducks behind the registrar’s office to happy-cry in private. “I’m finally someone’s wife at the age of 40,” she sobs as clutches her marriage certificate. “I’m finally a family’s daughter-in-law. Song Kang Sook, congratulations you bitch. Congratulations you crazy bitch!”

Like many people from fractured families, she craves family belonging. This is a uniquely humanizing moment, both in the context of the show itself and as a representation of stepmothers in Cinderella media overall. But Kang Sook’s history has taught her self preservation at any expense, and that turns her abusive.

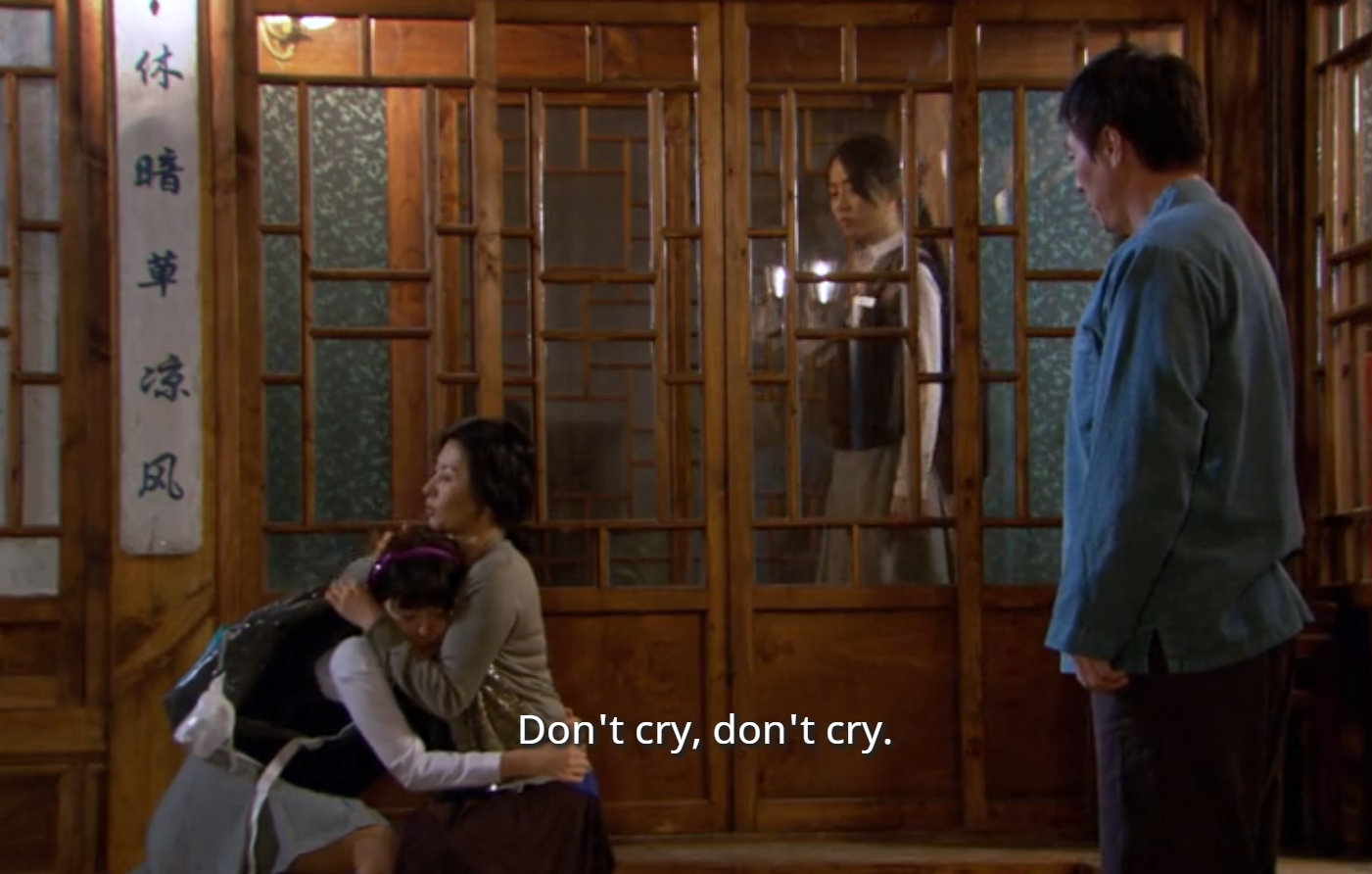

Hyo-sun believes her new stepmother’s lies about schoolyard gossip and gets into her dad’s alcohol (she’s a young teenager and Korean drinking age is twenty) to cope with the stress. After drunkenly yelling at their entire class reveals that no one actually cares what their last names are, she marches home to ask her stepmother why she said so. She’s socially inept enough to do this in front of her father. Eun-jo already has chronic irritation towards Hyo-sun and knows exposing her mother’s lies could put them out on the streets. So she sabotages the conversation by shoving her little stepsister to the ground. This is rough, yes, but Hyo-sun isn’t actually injured. Kang Sook slaps her own daughter and rushes to help Hyo-sun out of the dirt.

All this is a desperate ploy to stay in her new husband’s good graces. In a reversal of the typical Cinderella dynamic, Kang Sook makes a show of coddling Cinderella, even letting Hyo-sun fall asleep in her lap. Eun-jo walks in on this and feels ever the more alone.

This show masterfully fleshes out the fairytale archetypes without altering their overall roles. Cinderella is still an ingenue, but her innocence rings obnoxious. Eun-jo’s emotional distance and physical roughness are scary, but we in the audience understand her reasonings for being so. Kang Sook craves love and financial security, but she’s still villainous both in her manipulative coddling of her new stepdaughter and her neglect of her own daughter.

Media like this speaks to viewers whose complicated family relationships have no true villains, just a lot of people from broken families clashing against one another. But what about happy stepfamilies?

With the rise of second wave feminism in the sixties, divorce became more prevalent, creating more stepmothers and stepsisters. Producer Sherwood Schwartz was inspired to create his blended family comedy The Brady Bunch after reading that 31 percent of all marriages in 1965 involved a stepchild. A 1969 episode addressed one harmful stereotype rising from the Cinderella tale. Though the cast features three young girls-one of them named Cindy, of all things-the youngest son, Bobby, fills the Cinderella role.

In the tenth episode of the first season, Bobby and his stepsister Cindy watch a televised Cinderella portrayal. He is so distressed by the evilness of the stepmother that he switches the TV off, telling Cindy, “Boy, they can be mean.” Cindy argues that blended families aren’t so bad, saying, “Well, I’m not worried and I got a stepfather.” Bobby then unconsciously calls out the gendered implications of the narrative. “Whoever heard of a mean stepfather? It’s only the mother that’s famous for mean.”’

Seconds later, Carol comes in and innocently asks Bobby to help clean out the fireplace, inadvertently stoking Bobby’s fears. His older stepsisters, Marcia and Jan, are next to add to his Cinderella complex. Both Bobby and Jan receive hand-me-down clothes in this scene, but Bobby’s out of the room changing when Jan complains about hers. Bobby feels inappropriately singled out and looks frumpy-dumpy in his brother’s too-large shirt. He learns Jan and Marcia are headed to the movies (little boys aren’t into royal balls) and asks to join. Carol refuses him on the grounds that it would keep him up too late. Marcia adds insult to injury, teasing, “We coudn’t take you looking like that.”

“Of course not,” Jan joins in. “Who’d look at the screen?”

After his stepsisters enjoy a laugh at his expense, Bobby asks Mike if there’s any truth in the Cinderella narrative. He tells Bobby, “That story’s really given stepmothers a bad name.” The family’s housekeeper offers similar reassurance, but Bobby isn’t convinced. “Cinderella’s stepmother was real mean. I saw it on television with my own eyes,” he insists, alluding to the power television has to craft reality for children. Bobby is roughly eight years old and doesn’t yet have the lived experience of observing other blended families, or even exposure to other stepfamily media, so Cinderella wields a singular power. He decides his only course of action is to run away from home, armed with his brother’s suitcase and his life savings of $9.86. Fortunately, his brothers snitch to the grown-ups, and Carol brainstorms a way to show him he’s loved.

When Bobby hauls his suitcase downstairs to the front door, he finds Carol stationed there, holding a suitcase of her own. She explains that she loves Bobby too much to let him go alone and Mike will just have to raise the other five kids on his lonesome for a while. Naturally, the audience knows this isn’t a serious offer, but little Bobby takes it solemnly.

“Even though I’m only a step?” he asks.

“Listen,” she tells him, turning him around to face the stairs. “The only steps in this house are those.”

Mother and son then hug and dissolve into a 107 episode happily ever after. Within the scope of a two hour movie, viewers don’t usually get to see Cinderella and her stepfamily in a long term relationship. But the next several seasons give us a happy stepfamily portrayal, if an overly rose colored one. The Brady kids always call their new parents Mom and Dad, even in this episode, where Bobby is actively trying to run away from Carol.

This episode is a testament to the power television holds to sculpt reality for viewers, especially young children, who naturally turn to narrative to make sense of their worlds. All members of blended families experience an array of emotions, sometimes lifelong tensions but also love as well. It is important for media to balance portrayals of different members of the stepfamily, or at the very least, flesh out characters so viewers can remember their new families are composed of people who are all protagonists in their own life stories.