In an era increasingly concerned with all other forms of diversity, where race and ability and discussion of body image are becoming vital tools to “update” classic fairy tales, religion has actively swept under the rug. The bygone ages that birthed our fairy tales were highly religious. The ATU folk tale index documents almost a hundred fairy tales with titles like The Devil in Noah’s Ark or The Angel and the Hermit. But those tales aren’t the ones that make it onto the screen today. Our database does contain three devil stories, but they are soundly outranked by legions of princesses. Typically, the strongest presence of religion in fairy tale media is a priest standing behind a happily ever after couple as they say their wedding vows.

Taking Disney as a sampling, Snow White, the first princess, is shown saying bedside prayers for her prince and the dwarves in the 1937 film. But no ensuing Disney films incorporated Christianity beyond giving quick glimpses of wedding clergy or the bishop officiating Elsa’s coronation. That Elsa has a coronation at all (not all monarchs do) makes her abdication in the sequel problematic. Coronations are religious rites, after which anointed monarchs aren’t supposed to step down from their roles until death, which means Elsa has turned her back on a church as well as a nation.

New Orleans voodoo features as a spooky, villainous plot force in The Princess and the Frog, but wasn’t treated as a serious religion. We get a few quick mentions of Islam in both Disney iterations of Aladdin. The Genie of the animated film instructs the Sultan’s subjects to “brush up your Sunday salaam.” Salaam translates to peace and is used as a religious greeting, but the pairing with Sunday runs the risk of sounding, to viewers unfamiliar with the term, as if Genie is telling them to dress in their Sunday best. And Sunday is not even a holy day in Muslim culture. My Christian mother has often spoken on how she attended church on Fridays while living in Iran as a child, so I appreciated that the live action remake switched up the line to “brush up your Friday salaam.”

While raising secularism has turned religion into a diversity taboo in most modern media, one last vestige of Christianity remains in popular fairy tale adaptations: the godmother.

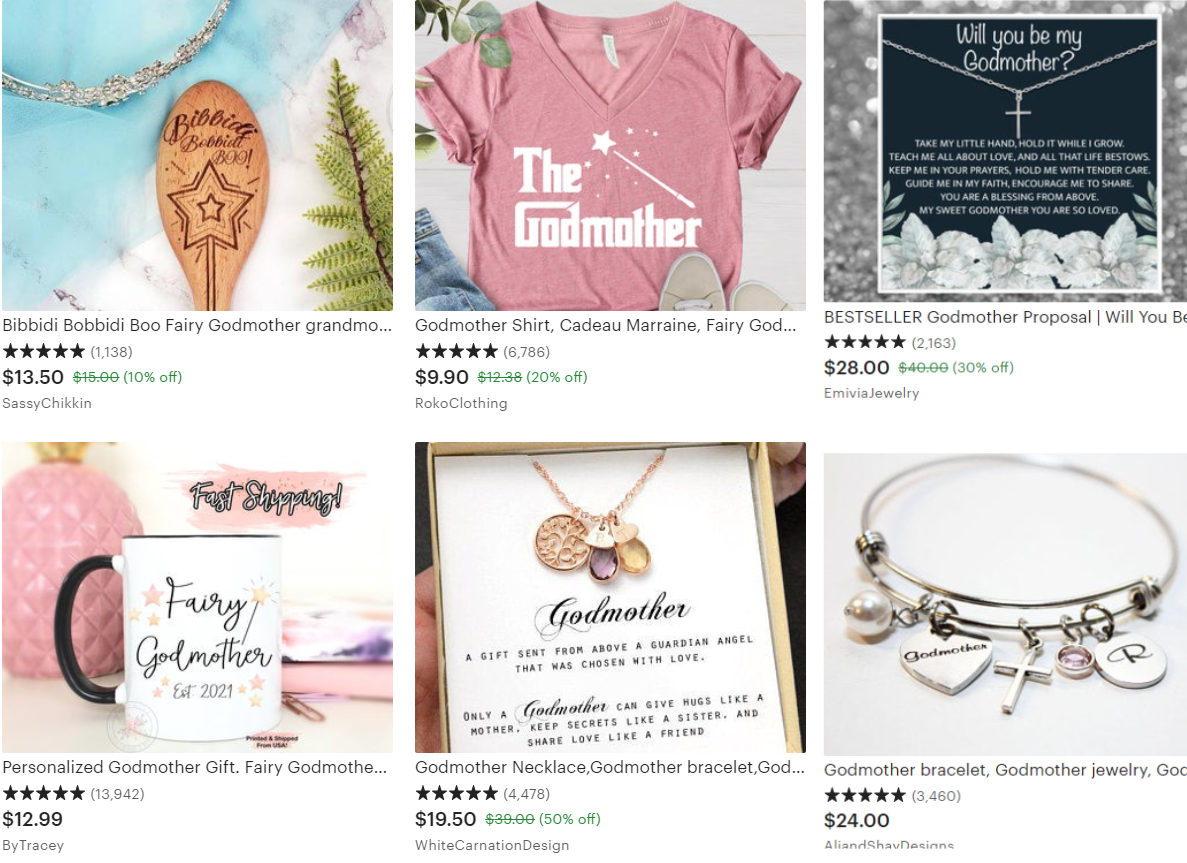

Viewers who don’t come from a religious tradition featuring godparents may only be familiar with the term at all thanks to Cinderella’s fairy helper (and perhaps Sirius Black, godfather to Harry Potter, who is never shown to be religious). In Catholicism and various other forms of Christianity that practice infant baptism, a godmother is a close family friend who attends a baptism, acting as a witness to the ceremony and doing things the baby can’t, like answering a question or handling a lit candle. Technically, a godmother is responsible for the child’s spiritual upbringing and should act as a mentor figure as the baby grows up. Some godmothers do stay involved for the long haul while others treat godmothering as a bridesmaid-like role where a woman has a brief ceremonial presence at a religious and social event but takes on no further obligation. And, like fairy tale godmothers, they may come bearing gifts. Etsy lists almost 40,000 results for godmother merchandise. Some are religious, baptism-themed keepsakes. Some are the sort of gear you’d buy for a fairy-tale themed party. Many could be used for either purpose.

It is in a gift-giving capacity that Sleeping Beauty’s fairy godmothers show up to her christening ceremony in the Perrault fairy tale The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood. The fairies are still there bestowing gifts in the 1959 Disney Sleeping Beauty, but the purpose of the ceremony and their role is only implied. They are not vocally referred to as godmothers. The narrator calls the occasion a “great and joyous day did all the kingdom celebrate the long awaited royal birth.” The event acts like a christening or baptism, but isn’t called such.

In both print and televised media, modern fairy godmothers don’t bother to show up to baptisms anymore. They tend to come from training academies or employment agencies. In young-reader books Phillippa Fisher’s Fairy Godsister by Liz Kessler, Janette Rallison’s My Fair Godmother, and the Disney film Godmothered, which has some similarities to Rallison’s novel, the fairies are students or young professionals who are assigned to clients to fix up their pathetic lives. Godmothered features Cinderella shout-outs like pumpkins, clocks, and ball gowns. A client-contractor relationship is one of strangers. You don’t need to answer the question of where, exactly, this fairy godmother has been for the entirety of the protagonists’ backstory.

The corporatization of fairy godmothers is indicative of both secularization and trends towards realism. If an adaptation takes a realistic tone, Cinderella’s having a kindly mother figure at all raises the question of why she doesn’t run off to live with the godmother instead of slaving away below the stepmother. Unless the godmother is supposed to represent something more.

A kindly figure with wings, who has hitherto not been part of your day-to-day life, motivated by pure benevolence, stepping in just when you need it most? That rings like a guardian angel. Hanna Seariac, a folklore researcher who was baptized Catholic and had godparents as an infant before later being baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, takes a religious interpretation of the Cinderella tale. She sees the prince as representative of the Prince of Peace, Jesus Christ, exerting a salvific influence in Cinderella’s life. “I think the fairy godmother is clearly like a guardian angel,” Seariac says, drawing comparisons between Cinderella’s salvation and Christ receiving strength from an angel in Luke 22. “The angel is sort of akin (to a fairy godmother) because the angel is preparatory, the angel prepares Cinderella to meet the savior in a lot of instances.”

Corporate fairy godmothers are anything but angelic.

In Fairly OddParents, godchild Timmy Turner and his fairies sometimes have to contend with devious, gray-suit wearing corporate pixies, who use their power for unfun purposes ranging from conquering the world to requiring all wishes to be submitted in paperwork format. Wanda, Timmy’s fairy godmother, sums them up by saying, “Pixies are just as magical as fairies but they treat magic just like a business.” Even the more fun-spirited fairies are bound by rules and frequently have to answer to their boss back in Fairyland.

Rocky and Bullwinkle’s Fractured Fairy Tales frequently takes comic, corporate interpretations of fairy tales. Cinderella’s godmother makes her sign a contract that requires her to pay back the makeover expenses before midnight. “Even we fairy godmothers have to make a living, you know.” The prince himself goes broke by midnight and the godmother hires him on as a door-to-door salesman. Another Cinderella sketch has Good Fairy Rentals charging Cinderella extra for add-on wishes. The fairy later marries (and hires) the prince herself.

A Sleeping Beauty sketch features a fraud of a fairy who claims to have charmed the princess asleep in attempt to cash in on the multi-million profits of Sleeping Beauty Land. She doesn’t admit her deceit until the tourist attraction goes bankrupt.

In Shrek 2, the business card-wielding corporate godmother is outright villainous. She headquarters herself in a giant factory, where she manufactures potions for profit, poses on billboards to promote herself, schemes to have her son replace Shrek as Fiona’s husband.

But no matter how corporate you make them, there’s that troublesome “god” prefix. Eleanor Bloomingbottom, the fairy of Godmothered, takes advantage of it to swear. She uses “oh my godmothers” and “What in godmother’s name?” alongside the normal “oh my goodness” and cutesy curses like “son of a butterscotch.” Eleanor is a young professional eager to assist a client, Mackenzie, so she can transition from godmother school to real godmothering. She is so rule-set in her idea of what a happily ever after should be, according to fairy tale tropes, that her magic shenanigans upend her client’s life rather than add more happiness. When a desperate Eleanor tells Mackenzie, “If I don’t get you to happily ever after, then I’ll have to spend the rest of my life as a tooth fairy,” Mackenzie calls her out on serving her own agenda. “This is all about you,” she says sadly. “All this time I thought you cared about wanting to make me happy and you just want it for you.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dtbbMddugE

Real-world companies have also capitalized on the fairy godmother image. A 2021 Super Bowl commercial featured “Fairy Godmayo” swooping in to save one man’s sandwich. Available at a retailer near you!

The modern fairy will not rush to a woman’s rescue unless there is something in it for her and the client has bothered to sign on the dotted line. When fairies incorporate, a beautiful message is lost, that perhaps a divine force could take interest in your petty mortal heartbreaks and hearts’ desires-without being paid.

Even in a secularizing world, religion can still mesh with fantasy tales. Jewish authors Naomi Novik and Gail Carson Levine did so with recent books. Novik’s Spinning Silver makes the heroine of Rumpelstiltskin Jewish while Levine’s The Lost Kingdom of Bamarre incorporates the biblical story of Moses into a Rapunzel retelling, since both stories feature children raised away from their birth parents. Stories that draw from religious roots, incorporate outright mention of real religion, and include subtle religious themes still have to capacity to create wonder in modern audiences. Even when parodied, villainized, and turned corporate, fairy godmothers hold inherent angelic power that speaks to a deep yearning of the human soul: the longing to have an otherworldly power sweep in to save the day with no motive other than divine benevolence.