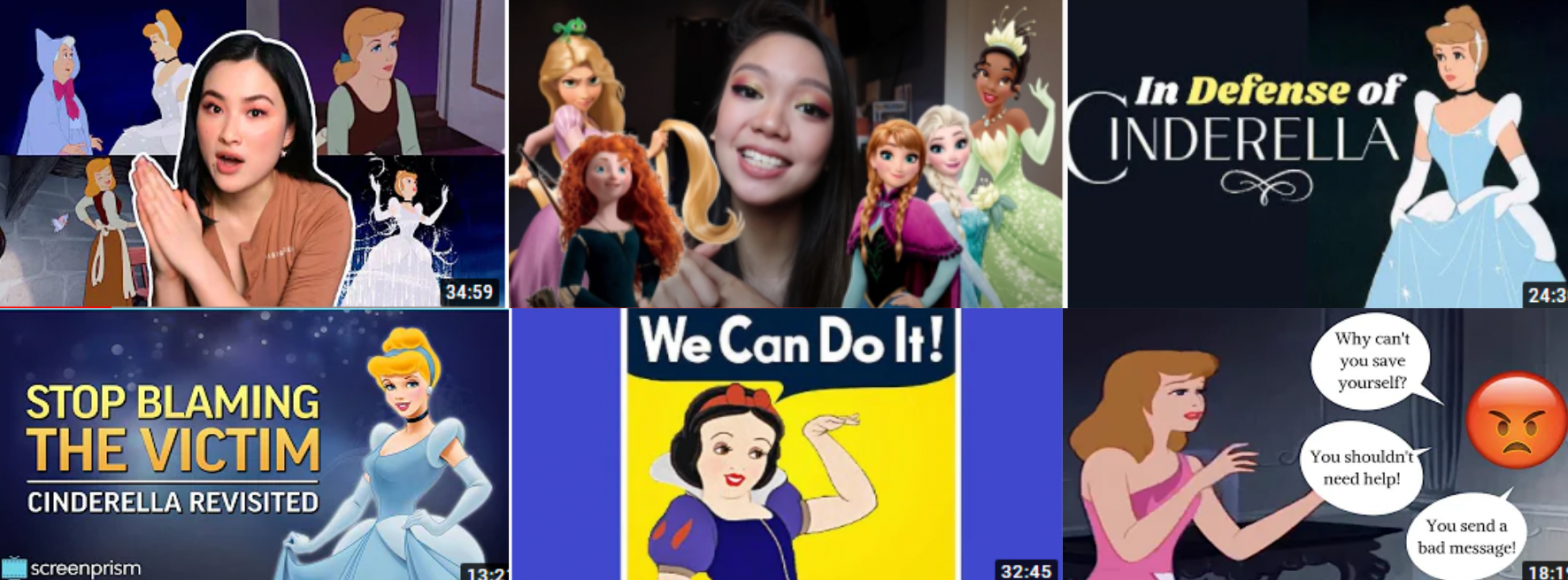

We’ve all heard criticisms of the Disney princess franchise and the sweet-as-cyanide messages of femininity and passivity they inflict on an unsuspecting girlhood audience. But as a child, I managed to adore the princess pantheon without succumbing to the “harmful” messages about gender roles and body image they supposedly embodied. It was only as a teenager in the early 2010’s that I became exposed to these ideas in the form of blog posts and articles, authored by women a generation older than me, telling me just how harm I’d survived in my childhood. Late-millennial, early-Gen Z women came of age steeped in both adults’ “everything-is-problematic” media analysis and nineties nostalgia. They were the toddlers who kept Disney in business every time they begged their moms for yet another plastic tiara. And now, those women are old enough to participate in the dialogue about the life-lessons of Disney princesses, and they do so as content creators in their own right. Many recent YouTube videos, mostly made by female YouTubers, bring a new perspective to the character analysis paid to Cinderella and Snow White: that these are positive characters who showcase a crucial kind of emotional strength.

In 2018, actress Keira Knightley stated on The Ellen Show that she banned her daughter from watching classic princess movies because the heroines aren’t good at escaping abusive situations. “She waits around for a rich guy to rescue her. Don’t. Rescue yourself! Obviously.”

Ellen’s studio audience reacted with applause. But the Tanner Twins, twin sisters who create the channel MJ Tanner, responded with a video called “A Defense of Disney Princesses and Movies.” The sisters don’t show their faces on camera, letting their voices play over film clips, making it hard to match quotes to speakers. One twin criticizes Knightley’s comment as victim blaming. “It’s not really something that people can just get out of and often times they do need help. There’s no shame in that, there’s no problem in that. And for (Knightley) to say like “Oh if you’re in an abusive situation or relationship, just rescue yourself, ‘obviously’ as if it’s something easy to do-”

“-that kind of made me uncomfortable,” her sister finishes.

Modern feminism is growingly concerned with discussing abuse and amplifying the stories of survivors rather than just pushing a vague notion of “being strong.” YouTuber Aiden Elizabeth delves further than the Tanner Twins in her close-reading of the film and analysis of Cinderella as an abuse victim. She categorizes the scene where Cinderella’s stepsisters strip off pieces of her dress as physical abuse, but reminds her audience, “No one’s abuse needs to be physical to be valid.” She says “the biggest critique that Cinderella gets as a character is…that she is a woman who lets people treat her badly. Cinderella is a great example of victim blaming.” While Cinderella’s character gets lambasted in analysis after analysis, “I have seen very few people talk about how abusive Lady Tremaine is. We are so busy getting angry at Cinderella for not leaving the household that we don’t get nearly angry enough at the actual abuser.” Aiden Elizabeth notes that Disney has made a concentrated effort to make more “strong” characters while “demonizing” women receiving help. “Something I think that we’re starting to neglect teaching little girls is that it’s okay to ask for help.”

In the same video, she celebrates Cinderella’s emotional strength, a sentiment echoed in a video by The Take titled Cinderella: Stop Blaming Victim. “It’s unfair of us to expect that Cinderella should be able to escape her situation sooner just by being a little bit sassier. She grows up in an abusive environment where she lacks all power. Her kindness and ability to cope through fantasy actually represent strength and bravery.”

YouTuber Amber Borden also adores the princess brigade and titles her video with the hashtag #stopdisneyprincessshaming. “When I was a kid watching this movie, their body image didn’t even cross my mind.” And as an adult, she says it “makes my blood boil” to hear them called bad role models for exemplifying stereotypically feminine traits. “In order to be a strong person, that doesn’t mean you have to be mean, catty, conniving, or manipulative.” As for the often-maligned Ariel giving up her voice for a man, “A lot of Disney princesses make sacrifices and that’s something that everyone does in their real world.”

It’s worth noting that the Disney princess franchise, begun in the year 2000, has endured in popularity as our culture has moved into an iconoclastic era. Disney simultaneously marketed Cinderella products–including sequels–while having their pop group The Cheetah Girls cover the Tata Young song ‘Cinderella’ to the point that many fans presume it to be originally authored for the girl band group.

I don’t wanna be like Cinderella

Sitting in a dark, cold, dusty cellar

Waiting for somebody

To come and set me free

I don’t wanna be like someone waiting

For a handsome prince to come and save me

Don’t wanna depend on no one else

I’d rather rescue myself

Liana C, a YouTuber who usually talks about makeup, fitness, mythology, and Asian representation, calls the Cheetah Girls song “exhibit A of Cinderella-shaming.” She, like other YouTubers, celebrates Cinderella’s hope and quiet strength and is troubled that criticisms center on Cinderella herself rather than Lady Tremaine. “Blaming the women who aren’t in this stereotypical girl-boss roles for being oppressed instead of blaming the oppressors is anti-feminist. Saying that she is a terrible example for girls for not standing up for herself is toxic feminism.” Perhaps Cinderella has historically drawn fewer defenders because her abuser is female, not male. A fan of the Cinderella sequels, where she forgives her stepsisters, protects them from danger, helps Anastasia find love, Liana calls Cinderella a great role model for her “kindness, strength, and capacity for forgiveness.” Critics who disdain fictional princesses as bad role models seem to forget that young girls live in a broader context and are more likely to look to their own mothers and grandmothers, not fictional women, for a model of how to act. Liana quotes her own family in reference to Cinderella’s kindness towards her mice. “One thing my grandma says is, ‘If you love them, they’ll love you back.’”

Cinderella isn’t the only early-Disney era princess to have drawn such defense. Why Snow White is (Still) the Strongest Disney Princess, a video essay by male YouTuber There Will Be Fudd, notes that Snow White, a Depression-era heroine, actually encapsulates the perfect message for a Depression-era audience: work hard and stay positive. And really, that is a good message for people in any time period. Recent Disney protagonists tend to be individualistic. The “big moment” of Frozen takes place when Elsa runs away from every responsibility and casts off her crown, an oh so expensive, possibly taxpayer-funded symbol of the duty she owes her country. Fudd points out that Aladdin wouldn’t have been received well by Snow White-era audiences. “If Disney had tried to lift America’s spirits with, say, a cocky, non-contributing pickpocket who thinks that being held responsible for criminal behavior makes him misunderstood he’d have been booed off the screen.” This narration is juxtaposed with a clip of Aladdin singing about how “There’s so much more to meee!” if only people looked closer. Depression-era audiences wouldn’t have been able to “sympathize with his sense of entitlement to be recognized for who he feels he is rather than what he actually does.” His five-star review of Snow White rates her as a survival icon. “For all her delicacy, Snow White is the epitome of American strength and resilience, a carefully constructed super soldier here to guide the nation through its darkest hours.”

Even the criticisms of Disney princesses, classic and modern, are relics of our own time-an age where much of hobbyist media analysis revolves around detailing why a popular work is problematic.

Identity politics were not en vogue when Snow White and Cinderella came into power. Nowadays, Fudd notes, an identity-based struggle is integral to the Disney princess character plot. “They can’t just have growth, they need a desire that’s specific to their identity..it’s tied into who they are and how they’re different from society.” He goes on to say that “the influence of these films is part of the reason that identity remains so prominent in media targeted at younger viewers.”

His narration about identity is played over a scene from Wreck-It Ralph 2 where a young girl takes an identity quiz to learn which princess best matches her personality (landing on Snow White). A significant advantage video essays have over print essays is the ability to flesh out a close-reading by juxtaposing video evidence while narrating their perspective.

Fudd ends the video by musing, “Will modern Disney films still hold up 83 years from now?” Will these self-interested, identity-absorbed princesses hold up when iconoclasm and identity politics have given way to some other zeitgeist? The classic princess, he believes, will. “Tough little Snow White will still be around. She’s a survivor and she’ll continue to enchant us for the same reason she always has: because she’s beautiful and kind and hard as nails.”

Nitpicking media for problematic qualities is an adult hobby, not a childlike pass time. In an era where everything is supposed to be problematic, labeling a beloved childhood franchise as harmful isn’t bold and radical anymore. These YouTubers represent a kind of New Sincerity. Writer David Foster Wallace characterized New Sincerity in a 1993 essay where he posited, “The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse” whatever they love, openly and frankly. If grown men and teenage boys could full-heartedly embrace My Little Pony in the brony phenomenon of the early 2010’s, why ever shouldn’t young adult women celebrate princess media that was actually marketed to them once upon a time? Princess-defender YouTubers came of age steped in fandom and nostalgia culture and everything-is-problematicism. They have the gut instinct to stan the media they loved as girls and the tech-savvy skills to do it.

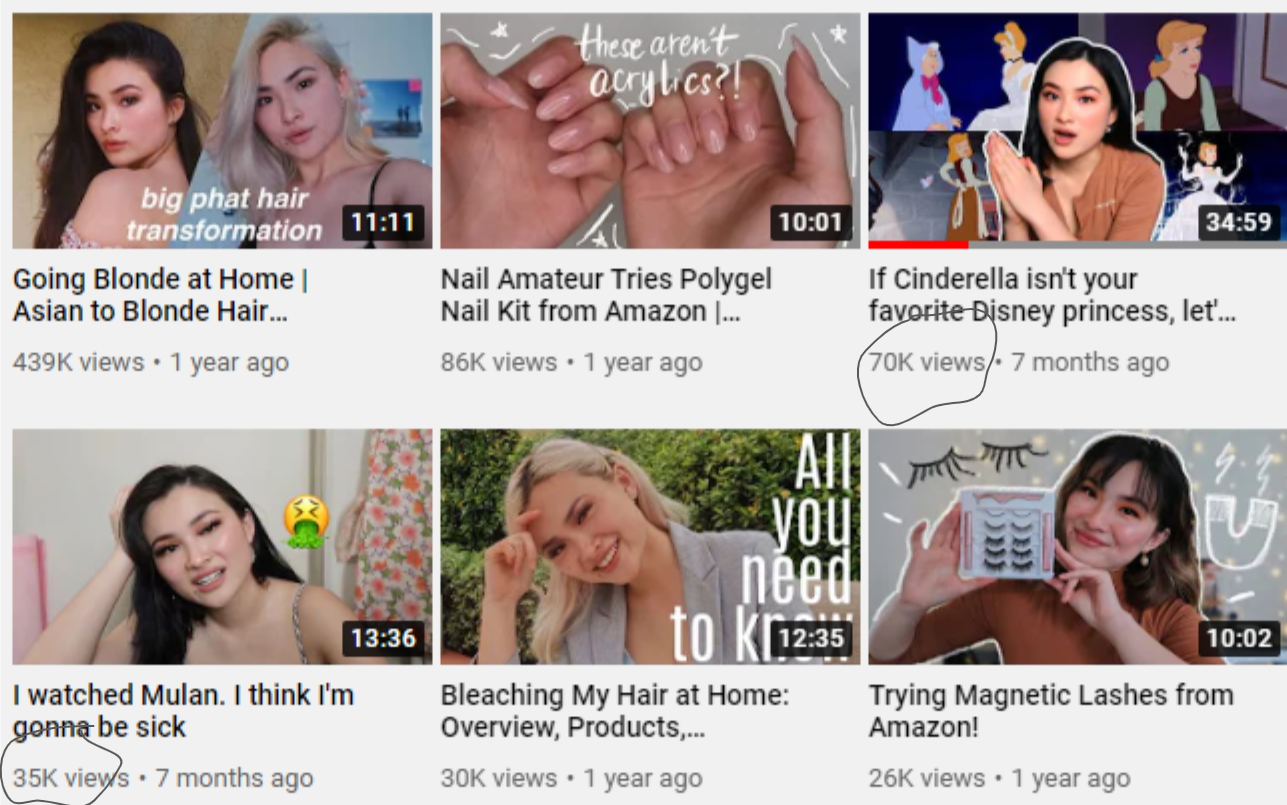

They enrich the familiar, never-ending dialogue about the worth of Disney princess stories by making valid points about emotional strength and old-fashioned resilience. Close-readings and analytical narration played over video clips are favorite techniques, as is a stylistic device where a computer scrolls through oh so many google results of Disney princesses being labeled problematic or anti-princess head clippings are piled on top of one another until the viewer feels overwhelmed. And these videos have hit home with a lot of people. Liana C, who is Asian, garnered 69,000 views on her video defense of “my girl Cinderella,” tens of thousands more views than her negative review of Mulan, proving that even an iconoclastic, remake-weary audience still cares to hear about why old things are worth liking. Admittedly, many pro-princess YouTubers have to portray Cinderella or Snow White as abuse survivor icons to make a case for them, demonstrating that “but it’s a good movie” isn’t compelling enough of an approach to draw an audience. YouTube’s algorithm naturally matches viewers with content that suits your search history, so even if you’re seeking out video essays that detail why Disney princesses are problematic, sooner or later, you run into analysis insisting they aren’t.

Whether YouTubers pay homage to the princess pantheon by tying them into crucial social issues like abuse or appreciate these films for their sincere themes, damsels in distress are no longer defenseless. These tales-as-old-as-time that made the leap from the page to the screen in the last century are poised to weather a century more, guarded forth by the little girls who once sang along to their songs as they twirled in front of the TV in trademarked tutus, and have not, as adults, stopped cheering on their favorite characters.