This post contains light spoilers for Raya and the Last Dragon. Proceed with caution.

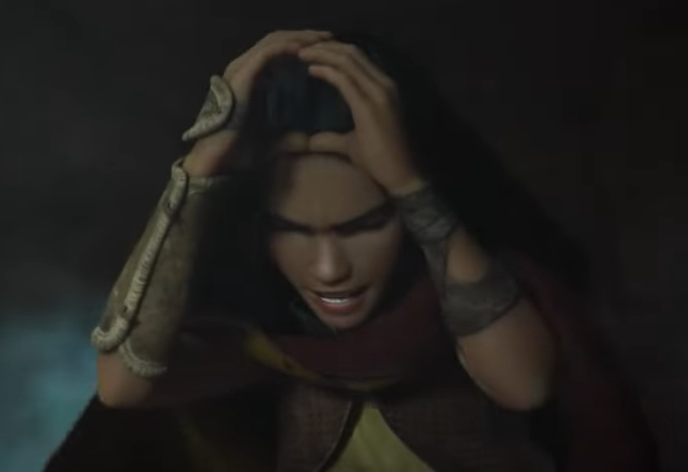

The dragon-worshipping nation of Kumandra finds itself entirely lacking in dragons after Sisu, the last of her kind, sacrifices herself to defeat the Droon, a malevolent black force that turns people to stone. Soon after, Kumandra is fractured into five feuding nations, each named after a dragon body part. All cool body parts like Talon and Fang, naturally. No one lives in the land of Pancreas. Raya, princess of the Heart people, befriends Princess Namaari of Fang during an international peace summit. After just one lunchtime together, Raya makes the judgment call of letting Namari into the stronghold where her tribe houses the dragon gem. The ensuing scuffle between the five nations shatters the gem and awakens the Droon, who turns Raya’s father (and many others) to stone. Six years later, Raya summons Sisu, a sleek and slinky creature who looks like the byproduct of Elsa mating with a unicorn Beanie Baby. They set off on a quest to recover the stolen gem fragments from the other nations, forming a “fellowship of buttkickery” with friends they meet along the way. Sisu’s open, trusting nature butts heads with Raya’s understandable distrust of other humans-especially Namaari, who has shown up again to stand in Raya’s way.

Released less than a year after the live action Mulan, the comparisons are inevitable, though the plot this time around is about restoring peace to a broken world rather than defending a homeland against invasion. Here’s how Raya stacks up to Mulan.

-

Getting it out there

First off, let’s talk about the release method. Disney upset audiences when they (understandably) wanted to turn a profit on a film they’d spent several years making and slapped a $30 price tag on Mulan’s Disney+ access. That might be a bargain for family movie night, but for a couple on a date? Nuh-uh. Disney chose to offer both theatrical and $30 streaming access this go around. When I booked tickets on opening day, my first-choice theater was sold out, demonstrating audiences’ desires to entertain themselves out of the house.

Theatrical release offered the chance to bait audiences with trailers. While governments continue to place barriers in the way of live-action filming, cartoons are having a heyday. Raya was largely animated from home, and so, presumably, were the various animated films showcased in the trailers (Cruella was the only live action one).While Pinocchio is technically live action, the star of the show is creepy, computer generated uncanny valley puppet. We will certainly see an animation boom for the next little while.

One curious side effect of the previews is that two of them use water as a catalyst for magic. A trailer for the upcoming Luca depicts two boys who turn into mermen when their skin touches water. The featurette Us Again showcases an elderly couple who dance in the rain when the water makes them young again. By the time we see a dragon with water powers, water-powered magic feels like a self-generated cliche.

-

Did not ground the story in one real culture

Mulan was left vulnerable to Chinese critics and other viewers familiar with Chinese culture who noted ways the film did not accurately depict Chinese history and culture. This is a sad amount of pressure to put on one work. Nobody expected Tangled to accurately depict medieval Germany, since we see representations of Grimm fairy tales all the time. I myself blogged about Mulan’s iffy portrayal of qi.

Raya, in contrast, takes inspiration from various Southeast Asian cultures (Laos, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Singapore, and Malaysia). As it’s a wholecloth creation–unlike Mulan, which drew from a traditional Chinese ballad–accusation of straying from the source text won’t be a problem either. This gave filmmakers more liberty to create worldbuilding that suited their story. In various cultures of Southeast Asia, people cup their hands as a show of respect. People of Kumandra circle their hands into what is supposed to be a gem shape as a deference greeting. This ties back into the culture’s obsessions with the dragon gem. Because Kumandra is not Thailand, it faces no pressure to accurately represent that one country’s culture.

-

The Heroine has an Actual Dragon Friend

At the time of Mulan’s release, I discussed how the live action film left her lonely and lacking in thematic development with no Mushu to talk to. Raya gets to go adventuring with Sisu. They pick up additional pals along the way, and Naamari was technically introduced first, but Sisu is undeniably her relationship character. She serves as a foil to help Raya explore the movie’s themes of trust and unity. While Raya’s warrior mentality dictates they charge into the other nations and take each gem fragment by force, Sisu always wants to present the chief with a gift and ask politely for the gem. Raya insists Sisu stay in her human form, arguing that a fractured nation given to in-fighting over a dragon gem would grow even more volatile over an actual dragon. This rings a little paranoid. Would a culture of dragon worshippers really deny a dragon whatever she asked?

-

Lets Raya Have A Warrior Arc-Kinda

Immediately after the prologue, Raya duels her father as part of a rite of passage to become the guardian of the dragon gem. She technically passes by placing one toe on the gem platform her father is keeping her from, but our girl’s been beat soundly. This sets her up for a warrior arc that was denied to the new Mulan, whose magic makes it so she no longer has to train up to match the men of the emperor’s army.

One would think that the next six years would hone her fighting skills. But after Raya loses an alleyway fight to a baby, her warriorness feels more like an aesthetic than a practicality. She comes equipped with a grappling hook, sword that splits like nunchucks, and combat sticks (called kali in the Philippines). Every pre-climax fight leaves Raya’s opponent victorious or gets interrupted. That’s not to say she’s incompetent. She’s skilled at using weapons to escape dangerous situations, just not for winning battles. She’s more of survivor than a fighter. While we see her be cool, the moment of triumph is a Moana-esque moment of forgiveness, so we never get the oomph of a final battle.

5. Explores a theme people actually need

I’ve discussed how Mulan injects artificial sexism to make its heroine “more” feminist and ends up with a nasty reverse effect. In a world where women can do pretty much anything-including lead the production of a movie-watching a woman triumph over old-school sexism does little more than remind us that sexism exists. Who needs that?

Raya’s release comes at a time when both the nation and the wider world are roiling over race issues and other forms of division. The film portrays a broken world and broken families. All the child members of Raya’s fellowship are orphans while Tong, an adult, lost his wife and child. The most disconcerting of these is Noi, a baby who is left fending for herself as a con artist after her parents are turned to stone. There is no shortage of adults among her people who could take care of her. Yet none of them do.

Noi and Raya initially meet when Noi mugs her in an alleyway. Yet Raya, an outsider who comes fully stocked with trust issues, and yet she makes the move of trusting her. This band of misfits from many nations become Noi’s temporary family until reunifying the dragon gem revives her real parents. Everybody could use this picture of cooperation between people of diverse nations and ages.

It’s sad that we didn’t get to see Raya strut her stuff as a warrior in climactic battle, but seeing a fighter turn to peace was probably the right call for a story about trust and unity. One side effect of Sisu’s repeated harping on goodwill, as well as Raya’s father’s peaceful nature, is that viewers are led to expect the inevitable kumbayah all along. Contrast that to Moana, which presented Te Fiti as a fiery villain before Moana restores her heart-gem in a move of reconciliation. There’s no feel-good twist climax here. Raya and the Last Dragon gets a good message across, but does so in a way at the expense of climactic oomph.

It would be superficial to set Raya and the Last Dragon alongside the live action Mulan simply because both films feature warrior women in Asian settings. More importantly, these films were released within a year of each other and faced similar audience expectations and venue challenges. Raya is a departure from recent Disney princesses. She’s called a princess in-universe, unlike Moana, who insisted she was only the daughter of the village chief. Her movie is not a musical, lending the work a more serious tone. Modern princess movies from Ariel onward typically feature individualistic princesses who made rebellion more of a perpetual cliche than docility ever was from the three Walt-era films. Raya and the Last Dragon synthesizes various real Asian cultures while purporting to be none of them and drives home a message about cooperation and unity over Raya’s own self-interested battle mentality.